June 2010

As usual, I had walked along the Thames Path from Sonning to Reading Station on a beautiful, sunny morning. The birds were singing, the ox-eye daisies were in flower and I heard my first cuckoo of the year. The black swan was sitting on her nest with her two cygnets close by. Also, close by was a heron, paying them rather too much attention.

I met Rosalind at Birmingham and we continued by train to Haltwhistle. The bus didn’t turn up at the scheduled time, but after a lengthy wait three came all together (Why do buses so often come in threes?). We alighted at Once Brewed Youth Hostel where we had booked a twin room. After cadging a teabag (not noticing the tea and coffee machine) we sat outside with our cups of tea, watched the lambs frolicking in the field and enjoyed being in the open countryside.

Our beds must have been comfortable because we were last down to breakfast next morning and nearly missed out on the grapefruit. It was a very good buffet and we smuggled out some bread and bacon to augment our lunchtime provisions.

Last to leave the hostel at about 8.30 am (not that late), we went up the hill to Hadrian’s Wall where the haunting cries of a curlew greeted us. Several other parties were travelling along the wall itself, but we had done that last year so marched along the military road instead, missing out most of the ups and downs.

At Sycamore Gap, where the Pennine Way leaves the Wall to head north again, we crossed the stile into new territory, leaving the other walkers to follow in the Romans’ footsteps.

The landscape changed to a mixture of coniferous forest, bog and open moorland without many distinguishing features. Alfred Wainwright was strong in his views that the Pennine Way should have ended on Hadrian’s Wall and that the Cheviot Hills further on should have had their own dedicated path. He hated conifer forests, but admitted that they were a life-line to districts where isolated villages were being abandoned through lack of employment in the area.

At intervals, we met a few other people on the clearly-marked path. A youth group was out for the day and an ex-policeman was accompanied by his son who had dodgy knees. When we stopped for lunch two more walkers passed by.

There was a welcome change in the scenery at Warks Burn, which was lined with deciduous trees. After we crossed the bridge we found a way down to the water’s edge where we took off our boots to paddle among the tiddlers.

The next mile or so was difficult to follow but we reached our digs at Heatherington Farm by 4.30 pm. No-one was about, elderly dogs and cats were asleep in the sun, abandoned tools were lying around. We sat on the verge of the quiet road to wait. At 5 pm a car drew up and a couple got out. ‘You’re not coming here?’ ‘Yes’. They had completely forgotten about our booking having spent the day with their grandchildren. The lady of the house recovered the situation very quickly, showing us to our room and producing some home-made biscuits. After a cup of tea, we were given a lift to Wark where we had an excellent meal at the local hostelry, even though the staff hadn’t been told that we were coming and were very busy.

Back at the farm we were invited to have a glass of wine with our hosts and we spent a pleasant evening putting the world to rights. Theirs had been one of the first farms to contract foot and mouth disease in the disastrous outbreak of 2001. The experience of having had all their animals slaughtered had been so traumatic that they no longer farmed, now concentrating on hunting and horse-racing. The time passed quickly, and it was gone 10 pm when we went to bed. Quite late for us!

The sun was shining again next morning, when we left after a leisurely breakfast just before 10 am. There was no hurry; we hadn’t far to go so could enjoy the lovely, pastoral Northumbrian countryside at our leisure.

We crossed the footbridge over Houxty Burn, soon coming to the unfortunately named Shitlington Hall, with Shitlington Crags behind. Scaling the crags was easy, and reaching the top we wandered across the pleasant moorland of Ealingham Rigg.

Coming down into the valley we crossed the bridge over the North Tyne into Bellingham. In a riverside park, families were sun-bathing on the bank. Children were playing in the water, their excited chatter and shrieks filling the air. We found a spare patch of grass and relaxed in the sunshine. All was right with the world.

After eating our lunch, we located the Cheviot Hotel where we were spending the night, leaving our rucksacks in our room. In the corridor outside was an enormous backpack. I tried to lift it up, but couldn’t. The owner must be having his kit carried for him. What would be the pleasure in exploring the beautiful British countryside with that albatross on one’s shoulders?

Our next objective was Hareshaw Linn. In the 19th century Bellingham had been a centre for iron production, and water from the Linn had supplied the iron works. As well as two blast-furnaces the Linn environs housed roasting kilns, coal stores and mining paraphernalia, as well as a store and a blacksmiths shop.

As we walked up the pretty dell to the waterfall, crossing and re-crossing the stream on ornate bridges and passing the overgrown entrances to the mine shafts, it was difficult to imagine it as the dirty, noisy hive of industry it once was. Today, it is home to over 300 species of rare fern and lichen. There are also red squirrels, although we didn’t see any.

When we got back to the hotel Rosalind realised that Verney had changed the settings on her camera, subsequently all her photos were in black and white. She wasn’t very pleased.

We had a good meal followed by an early night to prepare for a long, hot trek the next day. I had one of those nightmares where I’m in a familiar situation but everything that can possibly go wrong, does. I hoped it wasn’t a bad omen.

The owner of the massive rucksack appeared at breakfast. He was an Australian backpacker who was exploring this country and sleeping rough if accommodation wasn’t available. He wasn’t happy because he couldn’t find any shops that would provide things like split peas and lentils to make up his meals. In fact, he found very few shops, full stop.

The day promised to be a scorcher. We were away by 8.30 am, climbing steadily through fields to heather moors stretching as far as the eye could see. However, the path was boggy and indistinct in places making route-finding difficult.

We stayed above the 1,000ft contour for the next five miles, passing over Lough Shaw, Deer Play, Lord’s Shaw then Whitley Pike, where we slightly missed our way again, reaching a minor road 200 yards off course.

Just before the summit of Padon Hill we decided to stop for lunch. Two couples passed us, then the hatted Australian caught up, sinking to the ground for a rest. He was making good time despite his load, seeming little worried by the heat.

After Padon Hill there was a very steep, difficult ascent to Brownrigg Head, with a choice between plodding through the bog or scrambling along the top of a low, broken wall. We made it at last, stopping at the top of the hill to get our breath back. This gave our Australian friend time to catch us up again.

The descent through Rederdale forest was disappointing. The mature trees had been recently felled, the newly-planted ones giving no protection from the sun. The dusty, made-up track went on for ever and Rosalind got dispirited and tetchy. Of course, I was more stoical.

We stopped at the forestry picnic area where again the Australian caught us up. This time he plonked himself down, stating that he had had enough and was going to camp there for the night. Well, why not?

Our accommodation was a couple of miles further on, just past the village of Byrness along the River Rede. Consisting of two cottages formerly owned by the YHA, it was now an eco-friendly independent walkers’ hostel which recently had been refurbished to a high standard.

It was a warm, sunny evening. We joined other walkers in the garden for the take-away meal we had ordered earlier. The ex-policeman and his son with dodgy knees were there, also a talkative young girl who was taking a year out after qualifying to be a solicitor. She was spending three months of that year walking from Land’s End to John O’Groats. There were two other couples and we had a convivial evening.

Our attempt to have an early start next morning was thwarted because the door to the other cottage was locked so we couldn’t go in for breakfast. When we were finally admitted we had beans on toast and selected items for lunch from the ‘honesty’ shop. One of the couples we had met the previous night had been to the bothy on Great Lingy Hill above Caldbeck, read our note ‘Land’s End to John O’Groats the Pretty Way’ and had been most impressed. By chance they had overheard a remark and realised we had written it. I don’t think they were so impressed when they found out how many years the whole trip would take us!

The rain started as we climbed the steep path up into the Cheviot Hills. It was quite a scramble to the summit of Byrness Hill, but the gradients were gentler as we continued over Saughy Crag, Green Crag, Houx Hill then Windy Crag to Ravens Pike, at 1,700ft our highest point. The rain eased and Clare, the young solicitor, caught us up and walked with us across Ogre Hill. Even though the bog had mostly dried out, she managed to get a wet foot. Other than that, she was very competent, and we were glad of her company. It was very lonely up there in the mist.

We tracked the border between England and Scotland, passing the Roman fortlet and camp at Chew Green on the Roman road of Dere Street. At the Roman signal station, a mile further on, there should have been a far-reaching view across the Scottish border country, but we could see nothing. It was just as well that there was a prominent signpost where Dere Street left the Pennine Way to take us down into the valley. Although the path was marked on the map, it didn’t show on the ground, and we were glad of Clare’s GPS at one point to confirm that we were on route.

A little lower down a baby bird was struggling along the path. We hoped its mother would rescue it after we had gone.

Reaching the valley at Tow Ford, Rosalind and I stopped for lunch, saying ‘goodbye’ to Clare. We watched her striding off into the distance along Dere Street at a much faster pace, aided by her walking poles. Her next destination was Jedburgh.

It started to rain quite hard as we set off again up the road. The quiet lane along the valley had looked pleasantly rural on the map, following the banks of a meandering stream. But it wasn’t very pleasant. The newly-surfaced tarmac was enclosed, out of sight of the stream and had telegraph poles alongside. The six miles to Hownam seemed to go on for ever. To make matters worse the telephone box had been decommissioned and there was no mobile phone signal. Luckily a friendly lady with unfriendly dogs let us use her land line. We walked on until Jean from the Templehall Hotel picked us up near the junction where St Cuthbert’s Way climbed steeply up onto Grubbit Law.

Reaching the hotel at Morebattle our wet togs were taken away to dry. Hot showers were very welcome before we enjoyed our evening meal. We had a very early night. I was asleep by 8.15 pm!

Next morning, refreshed, we mentioned that as we had walked St Cuthbert’s Way some years ago, we were going to catch the bus to Melrose, thirty-two miles west, to continue our northward journey from there. We were informed that the bus company, First Group, was on strike. No buses were running that day.

... to be continued ...

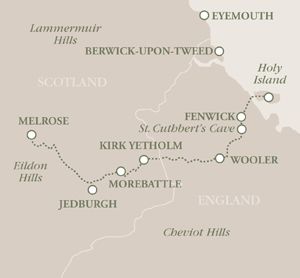

St Cuthbert’s Way

St Cuthbert was a 7th Century saint who started his religious life in Melrose Abbey and was buried 62 miles away on Holy Island, a centre for early Christianity. A long-distance-path, St Cuthbert’s Way was created to trace the saint’s many journeys between the two places.

In 2003 Rosalind and I had walked St Cuthbert’s Way, including paddling over to the island at low tide on the pilgrims’ route. We have incorporated the first half of that pilgrimage with our Land’s End to John O’Groats venture.

May/June 2003

Melrose to Morebattle

It had been very hot in Reading when I left, but by the time I had met Rosalind and we were in Berwick-on-Tweed it was drizzling. After a light meal, we caught the bus to Melrose. The weather improved on the way, but everywhere was very wet. Emergency vehicles were dashing in all directions along the roads, sirens blaring.

Reaching Melrose, we checked in at the youth hostel, bought something for breakfast and a packed lunch for the next day, then walked down to the River Tweed. It was a black, smelly torrent with tree branches being swept along, collecting other debris. On enquiry, we found out that earlier there had been a violent thunderstorm overhead which had lasted three hours! The Selkirk area had been badly flooded, with cars being overturned, structural damage and people being hurt. Rosalind and I have had a few wettings over the years, but we do seem to miss the worst of the weather.

There was an eclipse of the sun at 4.30 am next morning. We didn’t get up to see it, although there was supposed to be a clear view in Scotland. Much later, our breakfast of bacon sandwiches, fruit and yoghurt went down well.

It was a misty morning but promised to be a very hot day. Straight away, the path went steeply up through the gorse bushes, breaking through the mist near the top of the Eildon Hills. While we were up there we climbed the middle and highest of the three peaks where there was a welcome breeze. Our descent was shaded by trees; the tea house at Bowden in just the right place.

We were looking for the post office in St Boswells to buy some stamps, but missed it and ended up by the garage on the main road instead. Retracing our steps, we eventually found the post office, bought our stamps, replenished our water bottles at a tap and shared a large orange in the churchyard.

The River Tweed made a big loop to the north of St Boswells, the path beside it meandering up and down the river bank between trees and banks of wild flowers. The river had been right over the path in several places. The previous day we would not have been able to walk along it.

Our accommodation for the night was in a once-grand manor house with its own signpost. On the way there we passed the garage again. The main drive to the house was impressive. Rhododendrons were in flower in the lovely garden where the elderly dowager was weeding a flowerbed. The farm next door was run by her son.

Our room was old fashioned but very comfortable. The beds were provided with linen sheets which our hostess had ironed herself. After a luxurious soak in a full-length bath I helped to finish the weeding in return for a lift to the local pub (next to the garage on the main road). Our chauffeuse presumed that the bog-standard pub would be adequate for our needs, but then she gave me a quizzical look and said, ‘But one must never presume.’ We assured her that she had presumed correctly.

After enjoying our two starters we walked back to the manor house to explore the delightful garden accompanied by the neighbour’s dog, which soon got tired of our company and headed off back to the farm.

Next day, a couple who had been to a wedding joined us for breakfast. They were cyclists and would soon be returning to Edinburgh.

It didn’t take us long to re-join our path, which was lined with many unfamiliar plants. We passed an enclosure of rare and exotic turkeys, then an elaborate structure with a grotto, treadmill and a confusion of pipes had us mystified. We continued to Dere Street, which wasn’t the straight, Roman road that I was expecting but a pleasant, undulating wooded track which passed Lilliard’s grave. The inscription read:–

‘Fair maiden Lilliard

lies under this stane

little was her stature

but muckle was her fame

upon the English loons

she laid monie thumps

and when her legs were cuttit off

she fought upon her stumps’

Towards the end of Henry VIII’s reign the king of England wanted an alliance with Scotland and proposed a marriage between the infant Mary Queen of Scots and his young son Edward. This idea was rejected by the Scottish parliament and Henry declared war. This lead to a period of bloody conflict on the Scottish Borders. Lilliard was said to have fought in the battle of Ancrum Moor in 1545 after her lover had been killed. This time the Scots won the conflict, and for a time the English backed off.

A group of long distance yompers nearly mowed us down as they powered past. Six giants who were knocking off the 34 miles between Melrose and Kirk Yetholm effortlessly. We toddled on to Harestanes visitor centre to console ourselves with soup and treacle tart.

There was a new, wobbly suspension bridge over the River Teviot where we paused awhile on the river bank soaking up the sunshine. Sheep were munching close by, the sky a clear blue. Trees, reeds and a swan were reflected in the calm water.

Our B&B was on a minor road alongside the River Jed, a modern house with a balcony overlooking the river. We received a warm welcome from our kindly hostess who gave us a lift into Jedburgh for our evening meal (lamb shank), after which we walked the mile and a half back.

In the morning, I woke early and watched two rabbits demolishing the plants in the flower-bed underneath our window. At breakfast, I reported them to the landlady, who was amused. She said that the real battle was next door with the cabbages. Just before we left news came from next door that the rabbits had won the battle and the cabbages were no more. Our landlady thought this was hilarious.

We were back on route well before 9 am, soon marching along Dere Street again. We then came to a sign indicating that St Cuthbert’s Way had been diverted from Dere Street. Unfortunately, the new route was off our map, but as the path had been so well marked we followed the signs and hoped for the best. It worked out well despite my initial misgivings. The diverted route was very scenic, cutting out a lot of road, but it was quite hilly.

We re-joined the original way on the road just before Morebattle where we had several friendly waves from passing motorists. The local shop was open, so we stocked up with more bacon then had soup and a sandwich at the Templehall Hotel to fortify us for the big climb past Grubbit Law to Wideopen Hill. As the name suggests, there were superb views as we approached the top, with the Eilden Hills in the background and the Cheviots looming up before us. At 1,207ft this was the highest point on St Cuthbert’s Way, also the half-way point.

It was a pleasant walk down the hill but the road into Kirk Yetholm was a bit boring. Our destination was the youth hostel which amazingly we had all to ourselves, even though this was also the end of the Pennine Way. The warden was an earnest young man, very keen on ‘green’ issues. He had a large telescope which he used to survey the night sky. There was no problem with light pollution here.

After our meal, we asked him where we could go for an evening walk. He jokingly suggested that we should climb Staerough Hill (1,086ft). So, we did! After all, we’d only walked 16 miles.

It was well worth the effort. A badger was rootling outside the set and didn’t see or smell us for some time. When he did he shot down the hill like an arrow and disappeared out of sight. Then two deer leapt onto the ridge almost on top of us and were silhouetted on the skyline for a few seconds before turning and bounding off again. We watched the sun go down in a golden sky – wonderful.

The section of St Cuthbert’s Way from Grubbit Law onwards is not on our Land’s End to John O’Groats trek, but I had to record the whole day’s walk and I hope it was interesting.

Melrose to Edinburgh

We now come forward to June 2010 and return to Melrose by taxi from Morebattle to resume our journey.

It was a damp day, but the rain was mostly very light. From the start of St Cuthbert’s Way, we crossed the iron bridge and walked along the River Tweed, which was much more peaceful than the raging torrent it had been seven years ago.

We were following the Southern Uplands Way as far as Lauder. During a heat wave in 1989 I had spent five gruelling days walking 78 miles on this scenic but demanding coast to coast route from Portpatrick on the west coast to Cockburnspath on the eastern seaboard. My companion at that time, Jenny, lived in Edinburgh, and we hoped to meet up with her at the end of the trip.

The route kept to the high ground through undulating pasture where sheep were quietly grazing, only mildly curious about two solitary old ladies suddenly looming out of the mist then disappearing into the gloom. The hillsides were studded with golden gorse bushes, adding a touch of colour to the drab scene. We couldn’t find the Covenanters’ Well, marked on the map as a tourist attraction, but we did find a ‘waymerk’ cache, in this case a sculpture of a pair of feet.

As we weren’t walking the Southern Uplands Way and had no information about it, we didn’t realise the cache had been put there to indicate a place of historical interest (presumably the site of the Covenanters’ Well), and contained small, metal ‘waymerks’ There were thirteen waymerk caches along the route. Each walker was trusted to take one token from each cache, and if they were lucky it would have been a silver one. However, by the time we came across the cache the waymerks were no longer being minted, so it was probably empty.

We came down into Lauder, and as we had time to spare, we went into a café for a coffee and the best slices of apple pie that either of us had ever tasted. Mine was mouth-wateringly good.

Our luxurious accommodation was a little way out of the village centre on the main road to Edinburgh. It had all mod cons and more importantly, a large bath. Having made use of the facilities we crossed the road to the Lauderville Hotel for our evening meal. I enjoyed mine, but Rosalind’s lasagne was too rich for her. She had an uncomfortable night feeling sick and having nightmares.

The next day we were to follow our own route across the Lammermuirs and couldn’t blame anyone else if we got lost. We could have reached Edinburgh in a couple of days along the main road, but we didn’t consider that to be an option.

At Cairfreemill Hotel we thankfully left the busy A68 behind to begin our adventure by walking up the little road leading into the hills. Again, it was a bit damp, but the rain was light.

The birds were making an awful din. Oyster catchers, lapwings and curlews were circling above, screaming at us to keep away from their nests. There were many LBJs (little brown jobs) which we couldn’t identify and an unfamiliar raptor, possibly a female hen harrier.

The old drove road we were following passed close to the summit of Lammer Law which at 1,742ft is the second highest hill in the Lammermuirs and the best known. In the mist, we felt cut off from the modern world, imagining ourselves to be making this journey in prehistoric times. The dim outline of Hopes Reservoir down in the valley didn’t detract from the feeling of living in a bygone age.

The ancient track gradually descended to Long Yester, where baby rabbits were scuttling out of our way. Approaching the Yester Estate we were hopeful of finding a way in. When planning the route, I didn’t know whether this would be possible. There are no ‘rights of way’ as such in Scotland and in theory people may roam as they wish. In practice, landowners do not want people wandering all over their land and make it as difficult as possible for them to do so.

However, there were no obstructions in our way, so following a narrow, muddy path we entered a fairy glen beside the Gifford Water. After wandering beneath the verdant canopy, we came to more formal grounds, with manicured lawns surrounded by mature trees hundreds of years old. We then found ourselves walking down the main drive, passing Yester House itself.

I wondered aloud what we should do if the main entrance to the estate was locked. Rosalind gave me one of her withering looks, which she keeps for my most facile musings, and stated that we would knock at the door and ask to be let out. Of course. To my relief, the gates were open. As we passed through them I looked back at the ‘strictly private’ sign prominently displayed.

An avenue of magnificent lime trees lined the way into the little village of Gifford where we found our B&B in a comfortable, modern house. After an agreeable hot bath, we read up on some of the history of Gifford and the Yester Estate.

John Knox Witherspoon was born in Gifford in 1722. The son of the first minister of Yester Parish, he emigrated to America in 1768 with his family and became the first moderator of the Presbyterian Church. He was the only minister to sign the American Declaration of Independence in 1776 as a representative of New Jersey. When asked if it was the right thing to do, he is reported to have said that it ‘was not only ripe for the measure, but in danger of rotting for the want of it’.

The first castle on the Yester Estate was built around 1250. A later castle was built on the same site, leaving the underground part of the original castle intact. There is a large hall with a fireplace and two winding subterranean passages, one leading to a well called the Goblin Ha.’ This well has long been associated with magic and witchcraft.

In 1967 the estate was sold when the 12th Marquess of Tweeddale died and has had several owners since. The park was laid out in the second half of the 17th century so the majestic trees that we passed were over 300 years old.

Gifford had suffered a lot of damage the previous Christmas when heavy snow caused major landslips in the village and surrounding areas. Many trees had been blown down. Six months later the clean-up operation had barely begun.

In the morning, the breakfast was again excellent. I usually put on weight when on a walking holiday. I wonder why.

The next section of our journey was along the Pencaitland Railway Walk. Originally this was a branch line from Ormiston to Gifford, serving the many mines in the area. Now it had been made into a pleasant cycle and walkway with information boards set at intervals along the track-bed. It was drizzling again when we set out, but by the time we got to West Saltoun the rain had stopped. We were sheltered from the strong northerly wind, which was blowing blossom from the trees in bands across the path. The effect was very pretty.

It was not so around Ormiston where there were disused mine shafts, then an area of slag heaps. However, the scenery improved when we joined the River Esk walk and cycleway. There were good views of the Pentland Hills and our first glimpses of Edinburgh.

The riverside walk to Inveresk was very pleasant with a variety of plants along the banks. Inveresk is a picturesque village with a good number of 18th and 19th century buildings. We climbed up to the church and Oliver’s Mound from where there were far-reaching views over the Firth of Forth. Oliver Cromwell had his headquarters here in 1650, hence the name, but an older settlement dated back to the Iron Age. The Romans also used the Mound as a command post.

We continued to Musselborough, so named because of the mussel bank stretching out to sea. This is another community that is steeped in history. It is known locally as the ‘honest toun’. In the early 14th century Robert Bruce’s nephew, the regent of Scotland had a long, terminal illness, being cared for and guarded by the townsfolk, which earned the town that honour. On the way to our digs overlooking the golf course we passed the well-known Loretto School, the oldest boarding school in Scotland. The golf course itself is thought to be the oldest in the world. Records show that golf was being played on the links in 1672 and it is reputed that Mary Queen of Scots played there in 1567.

Reaching our accommodation, we phoned Jenny to arrange to meet the next day. At her suggestion, we went to the Italian Caprice for a tasty meal. On the way Rosalind and I had one of our rare disagreements. I wanted to cross the road at the lights, Rosalind wanted to stay on the sunny side of the street. Rosalind won. We walked in the sun until we had to cross, then took our lives into our hands and made a dash for it. When we arrived back at our digs we watched ‘Waterloo Road’ and ‘Junior Apprentice’ from our beds.

The huge breakfasts were becoming rather too much of a good thing. We couldn’t face anything cooked so had a substantial continental breakfast instead. As we were staying another night, we left our rucksacks in our rooms before walking along the beach to the Brunstane Burn walk and cycleway then followed the course of the Innocent Railway.

Opened in 1831, it was Edinburgh’s first railway. It started with horse-drawn carriages carrying coal to the city, but soon became popular as a people-carrier. The name came about because of the slow pace of travel. There were no stations on the way; passengers alighted when and where they wished.

The track-bed entered St Leonard’s Tunnel, the first public railway tunnel to be constructed in Scotland. Completed in 1830 this 517-metre-long tunnel was dug out of volcanic rock and lined with sandstone. Peering along its length we could just see the pin prick of light at the other end. It was damp and gloomy inside, but the ‘the light at the end of the tunnel’ became gradually closer until we emerged at the other end close to Arthur’s Seat.

This lump of rock, the remains of a 350-million-year old extinct volcano close to the city centre is 822ft high and a favourite tourist attraction.

Of course, we had to climb it. Blue sky appeared, and the sun came out. The gorse which covered the hillside was in bloom and there were great views in all directions.

All good things come to an end so reluctantly we made our way down to the city, consoling ourselves with some traditional Scotch broth followed by whisky fruit cake in a nearby cafe. We then walked along the Royal Mile to Waverley Station to complete this leg of our marathon.

There was just time for a city tour in an open-topped bus before meeting Jenny in the fruit market gallery. It was good to see her, but David, her husband, had had a stroke only a fortnight before. He was making good progress, but it was an extremely harrowing experience for them both.

However, we spent a pleasant hour with her before she returned to the hospital. With time to spare we sauntered around Princes Street Gardens, enjoying the sunshine before catching the bus back to our B&B in Musselburgh. Next morning, we returned to Edinburgh to catch our trains home.

In the evening, I walked along the river from Reading Station. Two black swans were keeping close guard over a solitary cygnet.