There were no problems on my journey to Edinburgh, but during the seven years since Rosalind and I were last here much has changed. We were hoping that Rosalind would be fit enough to walk some of the next section after treatment for her myeloma, but unfortunately it wasn’t possible. However, Jenny wanted to walk with me as far as Falkirk as she had never seen the Falkirk Wheel. Since David’s stroke she has had little opportunity to get out and about.

From Waverley station, I took a taxi to the imposing Georgian town house in Anne Street where she and David lived, clattering over the cobbled streets in this select area of Edinburgh. My bedroom was at the top of the four-storey building; the spiral staircase with wrought iron bannisters winding forever upwards.

After our evening meal of lamb hot-pot Jenny gave me the key to Dean Gardens, one of several privately owned green oases in the city. I spent a pleasant hour exploring the meandering paths through the semi-woodland on the steep slopes leading down to the Water of Leith, bubbling merrily over the rocks. Hidden birds were making their presence known by their distinctive songs; privileged birds to have such an exclusive habitat. I also felt privileged to be part of their world, if only for a short time.

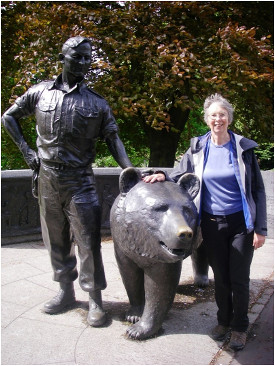

Before setting out on the walk proper, there was something I wanted to do in Edinburgh, so after a sustaining bowl of porridge for breakfast followed by a trip down to the fishmonger for a fresh sole for dinner, Jenny and I made our way to Princes Street Gardens. It didn’t take us long to find what we were looking for – the bronze statue of Wojtek the soldier bear.

Adopted as a cub by the Polish army in Persia, Wojtek grew up to become a fully enlisted ‘soldier’. Landing in Italy in 1944 he helped the Poles to breach the German defences of the Gustav Line in the Battle of Monte Cassino by carrying artillery shells to the foot of the mountain. Nearly a thousand Polish soldiers died as they fought their way uphill, yard by yard until the Polish flag was hoisted over the monastery ruins. Wojtek became the symbol of their heroism.

After the war, the Polish exiles were billeted at Winfield camp on the Scottish Borders where Wojtek became a firm favourite with the locals. Sadly, the day came when it was decided he needed a secure home which he was given in Edinburgh Zoo. He lived there until his death at the age of 22.

I had been following the story of the struggle to have a statue erected in Edinburgh to remember Wojtek and his Polish compatriots, so was pleased to learn that it had been finally unveiled in November 2015. I was even more pleased to have the opportunity of seeing the statue for myself.

David met us for lunch in the National Gallery, after which we had a look around, me trying to conceal my total ignorance from Jenny, who is an accomplished artist in her own right. Back home, Jenny coated the sole in breadcrumbs before frying it. Delicious! Afterwards she and David went to their Italian class where Wojtek the bear was the main subject of conversation.

Jenny had finished her jobs by 10 am so we said ‘goodbye’ to David and were soon walking beside the Water of Leith, leaving the bustle of the city behind. Little remains of the papermills that were once a feature along the river banks to remind us that Edinburgh was once the centre of a thriving industry. Further upstream work was being done to improve the flood defences, forcing us to leave the waterside on several occasions. Although the water level was low after several weeks of drought, heavy rain in the Pentland Hills sometimes caused serious flooding.

The impressive Murrayfield Stadium, home of Scottish rugby, has a capacity of nearly 70,000 spectators, but was deserted this morning as we passed it. On match days, it would be a very different story.

A little further on we reached the Slateford Aqueduct, towering above our heads. This immense structure carries the Union Canal over the Water of Leith. Before climbing the many steps to reach the canal we stopped at the visitor centre for a cup of coffee to fortify us.

The Union Canal passes through pleasant woodland, but Jenny brought it to my attention that there were no mature trees. With the coming of the railways, canals country-wide had been abandoned. This section had been filled in to accommodate new housing at Wester Hailes. It had been completely reconstructed at the turn of the century, Scotland’s most expensive millennium project.

Soon we crossed the Scott Russell aqueduct which spanned the Edinburgh City Bypass. Erected in 1987 at huge expense, this had been an act of faith that the canal would one day be restored. Now that the Union Canal is once again joined to the Forth and Clyde Canal thanks to the Falkirk Wheel, there is a through route for boats as well as a cycle and walkway joining the two cities of Edinburgh and Glasgow. Cyclists were making good use of the facility, so much so that we had to be on the alert to jump out of their way! The canal was not so busy. We saw only one barge in motion on the water.

Reaching Ratho, we had a drink at the Bridge Inn, sitting outside on the balcony while waiting for the bus. Here, there was more activity on the water. A party were boarding an excursion boat for a trip along the canal and several people were attending to their boats in the marina.

The journey back to Edinburgh was not straight forward. We explored every back lane, made a complicated circuit of the shopping complex, got stuck in traffic and had to change buses. If Jenny hadn’t been there I would have got hopelessly lost.

In the evening Jenny and David had a Pilates session. I declined.

Not wanting to repeat yesterday’s long bus journey, we hired a taxi to take us back to Ratho. It took a fifth of the time. The canal was shaded by more mature trees at first with glimpses here and there of the outside world; the motorway alongside as we crossed the aqueduct over the Cliftonhall Road; the long drop to the wooded banks of the Almond River at Lin’s Mill Aqueduct; the Pentland Hills appearing on the wrong side of the canal as we looped through Boxburn. The new Forth road bridge could be seen in the distance as well as the old Forth road bridge and the railway bridge. The new bridge was subsequently named ‘The Queensferry Crossing’ and opened by the Queen in September 2017.

The aspect opened out to reveal a major feature on the landscape, Greendykes Bing, a large spoil heap left over from the oil shale industry in the 19th and 20th centuries. East Lothian is the only area in Britain which has these Bings with their unique ecosystems.

At Winchburgh we left the canal for refreshment at the Tally Ho Hotel a little way down the road. The locals took great delight in exaggerating the distance we still had to cover before reaching Linlithgow, where we would catch the train back to Edinburgh.

We passed more Bings as we neared the village of Philipstoun, which for almost a century was a busy centre during the oil shale mining boom.

As we approached Linlithgow the canal and the railway converged. There was one more aqueduct, across the B9080, before we left the towpath to locate the station for our journey back to Haymarket. From there we hired a taxi to Ann Street. Jenny had slipped on a tomato the week before, wrenching her knee which was now swollen and painful. She hoped it would be better in the morning.

I was dispatched to buy massive portions of haddock and chips for dinner. The fish especially was delicious but there were plenty of chips left over.

Jenny had planned to come with me as far as Falkirk, but the morning brought no improvement in the state of her knee, so she decided not to risk damaging it further. She gave me a lift to Haymarket Station where we parted company. A train to Linlithgow came almost immediately so I was back on the canal towpath before 10.30 am.

The birds were again singing away merrily as I kept to the edge of the path to enable the cyclists to pass by unobstructed. My reactions tend to be too slow and Jenny wasn’t there to push me out of the way.

A nesting swan on the opposite bank was keeping a close eye on a rabbit grazing almost within pecking distance of her beak, a dangerous thing to do. There were many hedgerow and waterside plants along the way, many of which I couldn’t name.

All the way from Edinburgh there had been the occasional sign indicating that this was the John Muir Way. Just before the Avon Viaduct the Way left the Union Canal to descend to the Muiravonside Country Park. I also went down the steps into the green glen beside the meandering River Avon, a scene of peace and tranquillity.

There were more people as I approached the car park and visitor centre where I had a bowl of soup with my cup of coffee. Suitably refreshed I walked along the river a little way before climbing back up to the canal towpath to continue my walk, still on the John Muir Way.

The sense of being miles from anywhere was lost when the screen of trees suddenly gave way as the canal passed through an industrial estate, the path weaving between drab warehouses and piles of disused machinery. A little further on a large sign on H.M. Young Offenders Institution gave the number to ring in the event of an escape, highly unlikely from that formidable-looking fortress.

Happily, the ugly interlude was a short one: the tree screen resumed, and nature took over again.

As I approached the entrance to the Falkirk Tunnel notices warned that the tunnel would close in a couple of days for essential repairs. At least I’ve got my timing right.

The 696-yard-long tunnel was lit by fairy lights which reflected off the wet, hewn rock into the water below. The effect was surreal. Despite the lights it was dank and gloomy, the walkway was slippery, and I was glad of the hand-rail. There were constant drips through the rocks above which merged to become a waterfall as I reached the end of the tunnel. Indeed, it did seem that essential repairs were overdue.

Soon after emerging into bright sunlight I left the canal bank to navigate myself through the town to my B&B. The road did not seem long enough to have a no. 115 as there were no more than 14 or 16 small terrace houses each side. On closer inspection, I saw that each modest house was sub-divided into three or four even smaller units. No. 115 was a modern detached house at the far end which looked out of place. My accommodation was quite luxurious with separate bathroom and sitting room with TV, and of course the usual tea-making facilities.

Later I explored the town, choosing a pleasant bistro and bar for my evening meal of macaroni cheese.

The weather was clement in the morning although rain was forecast later. After a generous breakfast, I strolled through Callendar Park, passing a John Muir Way signpost to Callendar House. Brightly clad joggers were out on a fun run. They came in all shapes and sizes ranging from the super-fit to those who had difficulty putting one foot in front of the other.

Following directions to the canal I came to the towpath at the wrong end of the tunnel as I didn’t know the difference between north and south. Unsurprisingly, nothing had changed since I walked through it yesterday afternoon, but it was an experience worth repeating.

After another aqueduct there were two locks, the first ones encountered since leaving Edinburgh. As far as possible the Union Canal followed the contours of the land, with impressive aqueducts carrying it over the deeper valleys.

A sharp right turn took the canal through the Rough Castle tunnel under the railway and the B816. The tunnel is named after the Roman fort close by. A canal boat on a short excursion came through the tunnel behind me so I had the opportunity to photograph it going down to the Forth and Clyde Canal on the Falkirk Wheel, a drop of 79ft. Usually, the only boat going up and down on the wheel is the one taking paying passengers from the visitor centre who weren’t going anywhere.

After making use of the facilities at said visitor centre I started the second part of my journey along the Forth and Clyde Canal. It is wider than the Union Canal with more areas of marshland supporting a rich variety of wildlife, but by now light drizzle had given way to heavier rain so I hurried on to Bonnybridge to catch my bus back to Falkirk. From Bonnybridge a minor road over the railway gives access to Rough Castle and the Antonine Wall, but not for me today.

Later in the afternoon the rain cleared so I walked through Callendar Park to Callendar House to see the collection of artefacts excavated from sites along the Antonine Wall, also to learn some of its history.

In AD 142 Antoninus Pius ordered the Antonine Wall to be built as a replacement for Hadrian’s Wall to mark the northern frontier of the Roman Empire. Twenty years later it was abandoned, having become an expensive white elephant. The Wall was made of turf on a stone foundation so not much of it is left, but there are well-preserved sections of rampart and ditch both at Rough Castle and in Callendar Park.

Incidentally, the reason the Falkirk tunnel was built to take the Union Canal under Prospect Hill was because William Forbes, the owner of Callendar House in the late 18th century, would not allow the canal to pass through his estate.

There was a little residual rain when I woke up next morning but by the time I’d had my breakfast, bought something for my evening meal at Lidl and walked to the bus station, it had stopped. There was only one other passenger on the bus back to Bonnybridge who got off after a couple of stops. Luckily the bus driver told me when I had arrived. We had come a different way, so I didn’t register where I was. The empty bus continued its journey.

The next section of the canal roughly followed the course of the Antonine Wall but the forts and fortlets were all on the far side, so I passed them by. There are several locks on this canal but no impressive aqueducts. An information board by the towpath listed the wildlife that may be seen along the canal, especially nesting swans. There were several of these. A heron-like bird but with a cream breast was playing possum on the opposite bank. I thought it might be something exotic. After the trip, a friend identified it from my poor photograph as an immature cormorant. I’ve not seen one before.

The sun had come out by the time I reached Twechar in the early afternoon. There was plenty of time to climb Bar Hill (on the John Muir Way) to the Roman fort where there are traces of the Antonine Wall. The layouts of the fort itself as well as the bath-house are clearly defined. I continued to the top of the hill where a local was taking in the view, his two dogs sniffing around energetically. After exchanging a few words and appreciating the outlook myself, I went back down to Twechar Farm, my B&B. The cows with their calves were grazing outside my window as I enjoyed my picnic supper.

Rain was forecast for later in the day, galvanizing me to make an early start. A path through a narrow strip of bluebell wood provided an alternative to the canal bank as well as enabling me to peruse the farmer’s field where the site of a Roman fort is marked on the map. All I could see were the lush green shoots of a healthy-looking crop covering the area.

The town of Kirkintillogh encroached on the canal. Seats had been strategically placed for weary travellers to enjoy the view – of the barren walls of run-down buildings. A signpost indicated that there was a walking route to Milngavie via Milton of Campsie which with hindsight may have been better than my way (also shorter), but I would have missed visiting Cadder Church with its notorious churchyard.

At the beginning of the 19th Century this had been a popular place for body-snatching, the proximity of the canal making it easy to transport corpses to both Glasgow and Edinburgh for medical research. The problem was so great that a watch-house was built, and iron mort-safes were used to protect the bodies from misappropriation. These are still in the churchyard. The resulting shortage of cadavers may have incited the most famous of body-snatchers, Burke and Hare to resort to murder, in fact, 16 murders. When caught, Hare reneged on his partner-in-crime so escaped with his life. Burke was found guilty and hung, his corpse dissected, and his skeleton put on show in the Anatomic Museum of Edinburgh Medical School where it remains to this day.

Before long I left the Forth and Clyde Canal on what Google Earth had assured me would be a quiet country lane. Google Earth LIED. Not only was it a rat run to the A879 but was also the route to the tip and recycling centre. There was no walkway, so I had the choice of dodging speeding cars and rattling lorries on the tarmac or chancing my luck in the well-named Wilderness Plantation alongside the road. Rubbish littered the gutter and there was a stench of rotting flesh which got stronger as I approached the tip. Rosalind would NOT have been happy. For the last section I found a gap in the hedge and teetered along the uncultivated edge of a farmer’s field.

Finally reaching the main road, miraculously still in one piece, it was a short way along the pavement before an uneven path took me down to the Kelvin Walkway. For the first time since leaving Edinburgh I was bothered by biting insects, but compensated by the wide variety of marsh plants attracting numerous bees and butterflies. Across the river, at the site of another Roman fort, a treasure hunter was trying his luck with a metal detector.

After meandering for a mile or so the river turned back to go under the main road again. The Tickled Trout was close at hand, so I made a detour for a welcome break. The service was rather slow, and it was another hour before I was on my way again. Rickety steps, some broken, led me back down to the Walkway.

A mile further on a sturdy footbridge spanned the Pow Burn. It had been constructed in memory of SSgt Jim Prescott who died in the Falklands Campaign in 1982. The path was better maintained the other side of the bridge, enabling me to make swift progress to the outskirts of Milngavie where I was booked in at the Premier Inn. I had beaten the rain with time to spare. After a luxurious bath and looking forward to a relaxing evening, I turned on the six o’clock news. There had been a serious terrorist attack at an Ariana Grande concert in Manchester.

A first-class breakfast was provided at the Beefeater next door to the Premier Inn which was much appreciated. It was difficult handing my keys in at reception because of the pile of large pieces of luggage cluttering up the lobby. Their owners were about to set out on the West Highland Way, which Rosalind and I had walked in 2007. The baggage was being transported to their first overnight stop. I slipped my small rucksack onto my shoulders, retraced my steps to the river then went to find the station. Having time to spare, I wandered into the town. The West Highland Way brigade were taking photos of each other before setting off on their trek. There was a crowd of them, then they were gone, leaving the place deserted.

My journey back to Reading was uneventful, changing trains at Glasgow, Preston and again at Wolverhampton where I caught the Cross-Country from Manchester Piccadilly. The carriage I was in was nearly empty, reserved seats from Manchester not having been taken. Many young teens had been killed or injured in the terrorist attack. A sobering thought as the train brought me closer and closer to home.

Having been mostly on the John Muir Way from Slateford to Kirkintillogh, not knowing who he was, I thought I should do some research. From this I gleaned that John Muir was born in Dunbar in 1838, spent his boyhood exploring East Lothian then emigrated to the USA in 1849. Here he became a general good egg, especially in conservation, playing a large part in the preservation of areas of wilderness such as Yosemite and Sequoia National Parks. A 211-mile-long trail was set up in his name in Nevada. In the UK, the John Muir Trust is a conservation charity dedicated to protecting and enhancing wild places.

In 2010, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of his death, the John Muir Way was created. The 134-mile long-distance-path starts at Helensburgh on the east coast, ending at his birthplace at Dunbar on the opposite side of the country.